Tracing is a useful technique to find bugs in software, and ftrace is the tracing framework built into the Linux kernel.

But before we start talking about ftrace, let’s define what tracing is.

What is tracing?

Tracing is the specialized use of logging to record information about a program’s flow of execution.

You know when you add print messages in your code to debug it? You are tracing the application with your own “tracing system”. The debug messages added to the code are static tracepoints, and your “trace system” might send the debug messages to the program’s standard output or a log file.

Well, that works. But does not scale. Every time you want to trace some part of the code, you will have to add new debug messages and rebuild it. And you do not have much control over where the messages go. What if you want to save them to analyze later? What if you want to filter the messages? And the code will be a mess, with lots of print statements (you will have to be very careful to not commit any code with debug messages, right?).

The fact is that most of the time we don’t need to add debug messages to the code because there are already tracing tools and frameworks that can do that for us.

That’s where ftrace comes in…

What is ftrace?

Ftrace is a tracing framework for the Linux kernel. It was added to the kernel back in 2008 and has evolved a lot since then.

Ftrace stands for function tracer and basically lets you watch and record the execution flow of kernel functions. It was created by Steven Rostedt, derived from two other tools called latency tracer from Ingo Molnar and Steven’s logdev utility.

With ftrace you can really see what the kernel is doing. You can trace function calls and learn a lot about how the kernel works. You can find out which kernel functions are called when you run a user space application. You can profile functions, measure execution time and find out bottlenecks and performance issues. You can identify hangs in kernel space. You can measure the time it takes to run a real-time task and find out latency issues. You can measure stack usage in kernel space and find out possible stack overflows. You can really do a lot of things to monitor and find bugs in the kernel!

Black magic? Maybe a little. :-) But how does it work?

How does ftrace work?

There are two main types of tracing: static tracing and dynamic tracing.

Static tracing is implemented through static probes added in the source code. They have a low processing load, but the traced code is limited and defined at build time.

Dynamic tracing is implemented through dynamic probes injected into code, allowing to define at runtime the code to be traced. It has a certain processing load, but the range of source code to be traced is much larger.

Ftrace uses a combination of both static probes (function tracing, event tracing, etc) and dynamic probes (kprobes, uprobes, etc).

To trace function calls, ftrace will build the kernel with GCC’s -pg option.

When the kernel is built with -pg, GCC will prepend machine instructions to the prologue of every non-inlined function that will redirect the execution to the ftrace’s trampolines and tracer plugins that perform the actual tracing.

The disassembly listing below is the prologue of the function gpiod_set_value. The call to __gnu_mcount_nc on line 10 was added by GCC and will be used by ftrace to trace the function (this is the same technique used by gprof to profile user space applications).

|

|

Ftrace is also able to trace events in the kernel.

Events are static tracepoints added by developers to monitor kernel subsystems like the scheduler, power management, interrupts, networking, gpio, etc. Just search for functions starting with trace_ in the Linux kernel source code and you will find several places where trace events are used:

$ grep -R trace_ drivers/gpio/*

drivers/gpio/gpiolib.c: trace_gpio_direction(desc_to_gpio(desc), 1, status);

drivers/gpio/gpiolib.c: trace_gpio_value(desc_to_gpio(desc), 0, val);

drivers/gpio/gpiolib.c: trace_gpio_direction(desc_to_gpio(desc), 0, ret);

drivers/gpio/gpiolib.c: trace_gpio_value(desc_to_gpio(desc), 1, value);

drivers/gpio/gpiolib.c: trace_gpio_value(desc_to_gpio(desc), 1, value);

drivers/gpio/gpiolib.c: trace_gpio_direction(desc_to_gpio(desc), value, err);

drivers/gpio/gpiolib.c: trace_gpio_direction(desc_to_gpio(desc), !value, err);

drivers/gpio/gpiolib.c: trace_gpio_value(desc_to_gpio(desc), 0, value);

drivers/gpio/gpiolib.c: trace_gpio_value(desc_to_gpio(desc), 0, value);And how do you interface with ftrace?

When tracing is enabled, all collected trace data will be stored by ftrace in a ring buffer in memory.

There is a virtual filesystem called tracefs (usually mounted in /sys/kernel/tracing) to configure ftrace and collect the trace data. All manipulations are done with simple file operations in this directory.

And that’s one thing I like about ftrace. Since the interface to the tracing system is a file system, you can use simple tools like echo and cat to trace the Linux kernel!

So how do you use it?

How to use ftrace?

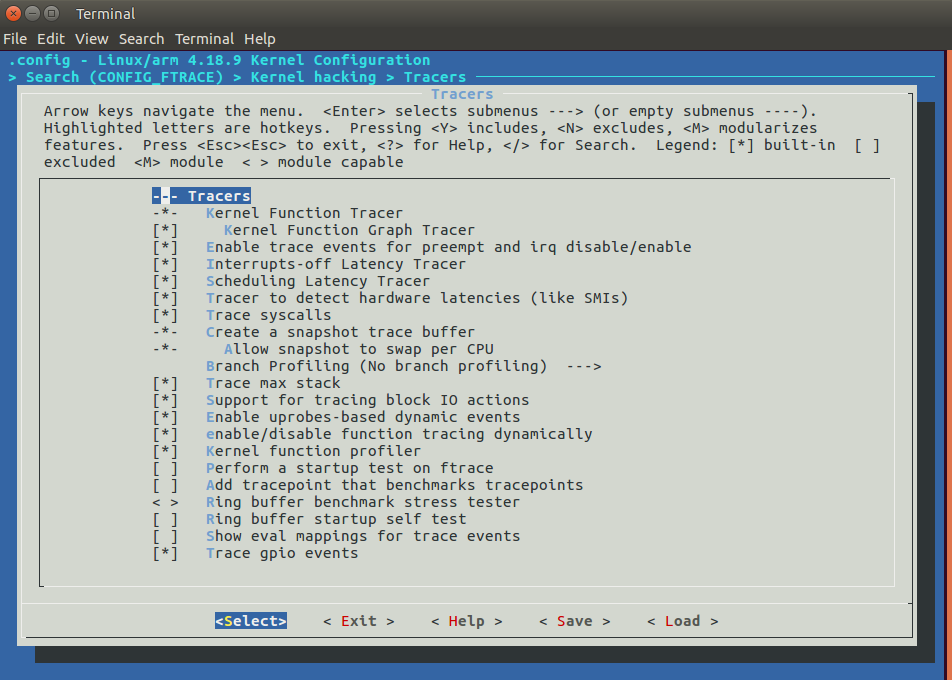

First, we should enable ftrace in the Linux kernel (CONFIG_FTRACE) and all tracers and options we plan to use. This is the menuconfig screen for kernel version 4.18 with most ftrace options enabled:

With ftrace enabled, we can mount the tracefs virtual filesystem:

# mount -t tracefs tracefs /sys/kernel/tracingAnd this is the filesystem interface provided by ftrace:

# ls /sys/kernel/tracing/

README set_ftrace_filter

available_events set_ftrace_notrace

available_filter_functions set_ftrace_pid

available_tracers set_graph_function

buffer_size_kb set_graph_notrace

buffer_total_size_kb snapshot

current_tracer stack_max_size

dyn_ftrace_total_info stack_trace

enabled_functions stack_trace_filter

events timestamp_mode

free_buffer trace

function_profile_enabled trace_clock

hwlat_detector trace_marker

instances trace_marker_raw

max_graph_depth trace_options

options trace_pipe

per_cpu trace_stat

printk_formats tracing_cpumask

saved_cmdlines tracing_max_latency

saved_cmdlines_size tracing_on

saved_tgids tracing_thresh

set_event uprobe_events

set_event_pid uprobe_profileWe can print the list of available tracers:

# cat available_tracers

hwlat blk function_graph wakeup_dl wakeup_rt

wakeup irqsoff function nopThere are function tracers (function, function_graph), latency tracers (wakeup_dl, wakeup_rt, irqsoff, wakeup, hwlat), I/O tracers (blk) and many more!

To enable a tracer, we just have to write its name to current_tracer:

# echo function > current_tracerAnd we can read the trace buffer with the trace or trace_pipe file:

# cat trace

# tracer: function

#

# _-----=> irqs-off

# / _----=> need-resched

# | / _---=> hardirq/softirq

# || / _--=> preempt-depth

# ||| / delay

# TASK-PID CPU# |||| TIMESTAMP FUNCTION

# | | | |||| | |

<idle>-0 [001] d... 23.695208: _raw_spin_lock_irqsave <-hrtimer_next_event_wi...

<idle>-0 [001] d... 23.695209: __hrtimer_next_event_base <-hrtimer_next_event...

<idle>-0 [001] d... 23.695210: __next_base <-__hrtimer_next_event_base

<idle>-0 [001] d... 23.695211: __hrtimer_next_event_base <-hrtimer_next_event...

<idle>-0 [001] d... 23.695212: __next_base <-__hrtimer_next_event_base

<idle>-0 [001] d... 23.695213: __next_base <-__hrtimer_next_event_base

<idle>-0 [001] d... 23.695214: _raw_spin_unlock_irqrestore <-hrtimer_next_eve...

<idle>-0 [001] d... 23.695215: get_iowait_load <-menu_select

<idle>-0 [001] d... 23.695217: tick_nohz_tick_stopped <-menu_select

<idle>-0 [001] d... 23.695218: tick_nohz_idle_stop_tick <-do_idle

<idle>-0 [001] d... 23.695219: rcu_idle_enter <-do_idle

<idle>-0 [001] d... 23.695220: call_cpuidle <-do_idle

<idle>-0 [001] d... 23.695221: cpuidle_enter <-call_cpuidleThe function graph tracer is an alternative function tracer that traces not only the function entry but also the return of the function, allowing you to create a call graph of the function flow and output the trace data in a C-like style with information about the duration of each function.

# echo function_graph > current_tracer

# cat trace

# tracer: function_graph

#

# CPU DURATION FUNCTION CALLS

# | | | | | | |

0) 1.000 us | } /* idle_cpu */

0) | tick_nohz_irq_exit() {

0) | ktime_get() {

0) 1.000 us | clocksource_mmio_readl_up();

0) 7.666 us | }

0) + 14.000 us | }

0) | rcu_irq_exit() {

0) 1.334 us | rcu_nmi_exit();

0) 7.667 us | }

0) ! 556.000 us | } /* irq_exit */

0) # 1187.667 us | } /* __handle_domain_irq */

0) # 1194.333 us | } /* gic_handle_irq */

0) <========== |

0) # 8197.333 us | } /* cpuidle_enter_state */

0) # 8205.334 us | } /* cpuidle_enter */

[...]Since you are going to gather a lot of data with ftrace, there are several options set up filters. For example, you can set up a filter to trace only a small group of kernel functions. Or you can filter by PID and trace kernel functions called only by a specific process.

In the example below, we are tracing only functions from an RTC device driver:

# echo "snvs*" > set_ftrace_filter

# echo function > current_tracer

# cat trace_pipe

Binder_3-836 [000] ...1 5890.663049: snvs_rtc_set_time <-rtc_set_time

Binder_3-836 [000] ...1 5890.663063: snvs_rtc_enable <-snvs_rtc_set_time

Binder_3-836 [000] ...1 5890.663106: snvs_rtc_enable <-snvs_rtc_set_time

kworker/0:0-2128 [000] ...1 5890.663215: snvs_rtc_read_time <-__rtc_read_timeYou can also enable just specific events like scheduling or system calls. In the example below, we are tracing only GPIO events:

# echo 1 > events/gpio/enable

# cat trace_pipe

mmcqd/2-103 [000] d..2 778.002889: gpio_value: 73 get 0

mmcqd/2-103 [000] d..2 778.002910: gpio_value: 73 get 0

mmcqd/2-103 [000] d..2 778.007575: gpio_value: 73 get 0

mmcqd/2-103 [000] d..2 778.013398: gpio_value: 73 get 0We can also use ftrace to measure latencies in kernel space like how long interrupts are disabled or how long it takes a (real-time) process to run after it is woken.

It is nice to be able to use simple tools like cat and echo to trace the Linux kernel. But sometimes we have to write to several files to set up a tracing session. In that case, we can use the trace-cmd tool.

trace-cmd tool

trace-cmd is a user-space command-line tool for ftrace created by Steven Rostedt.

It is a front-end to the tracefs filesystem and can be used to configure ftrace, read the trace buffer and save the data to a file (trace.dat by default) for further analysis.

# trace-cmd

trace-cmd version 2.6.1

usage:

trace-cmd [COMMAND] ...

commands:

record - record a trace into a trace.dat file

start - start tracing without recording into a file

extract - extract a trace from the kernel

stop - stop the kernel from recording trace data

restart - restart the kernel trace data recording

show - show the contents of the kernel tracing buffer

reset - disable all kernel tracing and clear the trace buffers

report - read out the trace stored in a trace.dat file

stream - Start tracing and read the output directly

profile - Start profiling and read the output directly

hist - show a historgram of the trace.dat information

stat - show the status of the running tracing (ftrace) system

split - parse a trace.dat file into smaller file(s)

options - list the plugin options available for trace-cmd report

listen - listen on a network socket for trace clients

list - list the available events, plugins or options

restore - restore a crashed record

snapshot - take snapshot of running trace

stack - output, enable or disable kernel stack tracing

check-events - parse trace event formatsFor example, the command below will start a function tracing:

# trace-cmd start -p functionAnd the command below will trace GPIO events:

# trace-cmd start -e gpioWe can also trace a specific process and record the tracing data to a file:

# trace-cmd record -p function -F ls /

plugin 'function'

CPU0 data recorded at offset=0x30d000

737280 bytes in size

CPU1 data recorded at offset=0x3c1000

0 bytes in size

# ls trace.dat

trace.datWe can show the tracing data with the report command:

# trace-cmd report

CPU 1 is empty

cpus=2

ls-175 [000] 43.359618: function: mutex_unlock <-- rb_simple_write

ls-175 [000] 43.359624: function: __fsnotify_parent <-- vfs_write

ls-175 [000] 43.359625: function: fsnotify <-- vfs_write

ls-175 [000] 43.359627: function: __sb_end_write <-- vfs_writeOr we can open it with KernelShark.

KernelShark

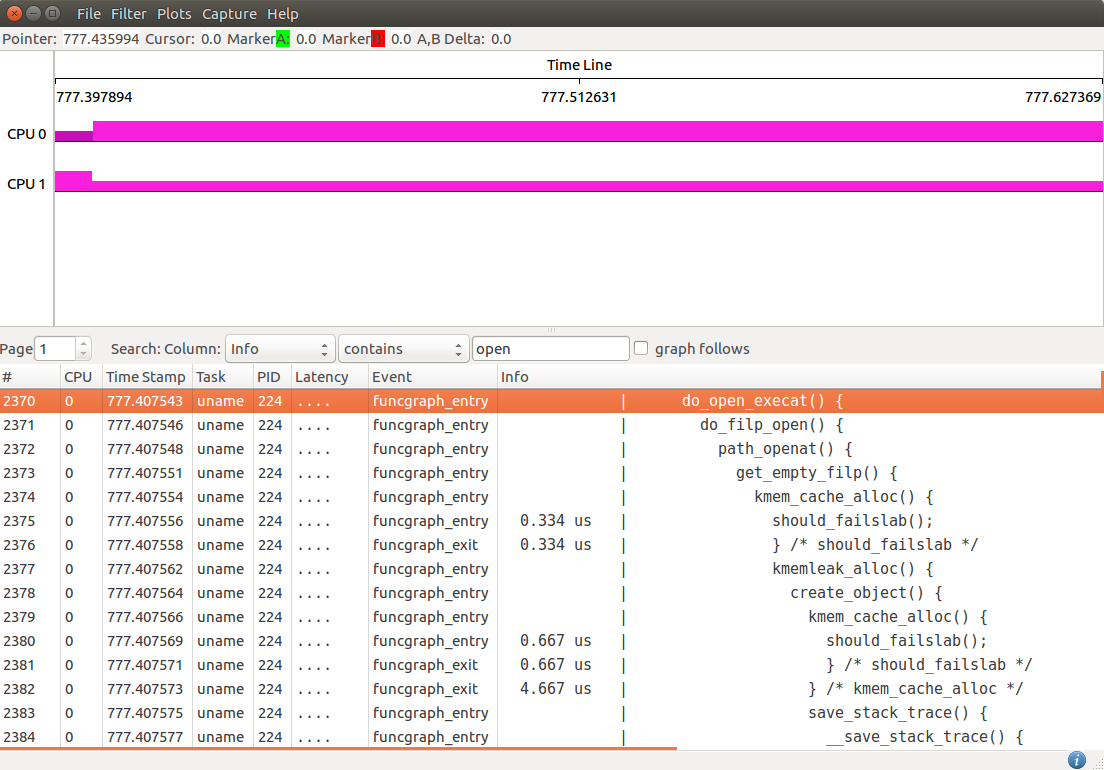

KernelShark is a graphical tool that works as a frontend to the trace.dat file generated by the trace-cmd tool.

The application has two main viewing areas. The top half is a graphical display of the data and the bottom half is a list view of each event.

The graph view shows graphical plots of the data (per CPU or task). You may zoom in or out into a given location to see the details of events on a specific time frame. The list view in the bottom half has filter options to help analyze the trace data.

More information is available in the KernelShark documentation.

We have seen here trace-cmd and KernelShark, but many more tools use ftrace nowdays, including perf and kernel live patching implementations.

If you want to know more, read the Linux kernel tracing documentation and the ftrace documentation.

There are also very good talks on YouTube by Steven Rostedt, including Understanding the Linux Kernel via Ftrace, See what your computer is doing with Ftrace utilities, Learning the Linux Kernel with tracing and ftrace: Where modifying a running kernel all started.

Although this article does not explore ftrace in detail, it is the basis for future articles where I will explore ftrace to measure latencies and identify different kind of problems in kernel space.

About the author: Sergio Prado has been working with embedded systems for more than 25 years. If you want to know more about his work, please visit the About Me page or Embedded Labworks website.

Please email your comments or questions to hello at sergioprado.blog, or sign up the newsletter to receive updates.